Morning Questions

Now that they are older, they wake up at a reasonable hour, something later than eight o’clock and occasionally after nine in the morning. (Well, until school starts tomorrow.) They totter down the stairs with that first-steps-in-the-day stiffness; their thumping like a gentle alarm clock alerting me that they are awake and they are coming my way. Then appears one of them – it could be either of the girls, though Short-pants is prone to rising earlier – pushing open the door to our bedroom, which sticks and sometimes requires serious muscle. A little sprite appears, donning just a pair of pink Cinderella underwear, lifts up the white comforter cover and crawls in between the sheets for the morning cuddle. It might be moments later – or as long as an hour – when the other one arrives and squeezes into the bed on the other side of me.

These cuddles are mostly wordless, except for the three questions:

Did you sleep well?

Did you have any good dreams?

Did you wake up feeling loved?

Short-pants adores the ritual of this Q&A, and answers each one with a deliberate “Yesssss,” letting the s stretch out for emphasis. I rarely ask Buddy-roo; before I even finish the first question she interrupts, “I don’t want you to ask me those questions.” I’ve asked her why not, dozens of times. The best I can get out of her is that she just doesn’t like them. So we cuddle in silence.

I’m struck by how the character of the morning cuddle has transformed over the years. When they were babies, this was the moment when they took my breast for the first meal of the day while I savored those last minutes of precious sleep. Then they were toddlers and we were constantly at war, fighting to keep them out of our bed until the sun had risen (our line in the sand), when the morning cuddle revealed the true pyrrhic nature of all those little battles we’d won the night before. This morphed into another stage in which their arguing, despite our admonishments, would crescendo into tearful screaming matches about who got to be on what side of the bed next to which parent – a prize that was hard to predict because De-facto and I never knew which of us was the coveted parent and we could fall out of favor at the drop of a hat.

Until now, a new phase, when they seem very content to wake up slowly, rising softly and silently and joining us in bed with little expectation of conversation, just the warmth and comfort of their parents and another twenty minutes of dream-time and morning slumber. (This is a great phase.)

I came across a photograph of my mother that I took a little over a year ago. Aware of her impending departure, I tried to capture little vignettes of her – things I wanted to remember – like the expression on her face while she washed the dishes (I snapped this without her noticing, from outside the window above her kitchen sink), or seeing her seated in her designated place at the head of the dining room table or curled on the couch watching television with her eyes closed. One morning I even photographed her sleeping in her bed, with her back toward me. I realized I didn’t have a strong memory of her sleeping alone in her bed; when I lived at home my father was usually beside her. Then there’s this: she was always up earlier than me. I never saw her sleeping in. Until that morning.

I took note of the details: the color of her tousled hair, the lace trim of the familiar nightgown against the skin on the back of her neck, her hand raised next to her pillow, clutching a piece of Kleenex. After I took the photo, I lifted the covers and slipped into bed beside her and put my arm around her. I wished somebody else was there to take a picture of the two of us in our morning cuddle so I could show Short-pants and Buddy-roo.

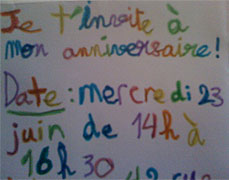

Instead I told them about it, which I suppose is even better because they had to conjure up their own image of the occasion in their minds. This prompted an inquisition: When you cuddled with Grammy, did she ask you the morning questions? No. Why not? I made them up for you. You made them up for us? Yes. Why? I don’t know. But why? I guess maybe to ease gently into using words after a long sleep. Gently? Why gently? (You see where this is going.)

This morning, they arrived within minutes of each other, their long, lithe bodies quickly snapping up the covers and diving into bed with us. We dozed in and out of the velvet pocket of morning sleep. When it felt like enough time had passed for words, I ran through the three questions with Short-pants. She answered with an emphatic and serpent-like “Yesssss,” pulling her arms tighter around me with each response.

I know Buddy-roo hates the questions but I keep thinking maybe someday she’ll change her mind and share this little ritual with us, and remember it later in her life as a good moment in her childhood. So occasionally I try them out on her anyway. This morning I braced myself for her usual scorn, but instead – surprisingly – she answered me.

Did you have a good sleep? It was okay, except it was too hot in my bed. Do you have any good dreams? I don’t remember if I dreamt or not. Did you wake up feeling loved? Maybe, if there are pancakes for breakfast.

Not so gentle, but not a bad way to start.