Solemn Fold

I pinched the frozen clothespins to liberate the sheet from the line of rope that spans the back porch. The sheet was ice-cold; it’d been hanging outside on the porch all afternoon. I wrapped the yards of damp cotton over my shoulder, trying not to drag anything on the floor as I pulled the rest of the laundry – pillowcases and a few dishtowels – off the line and made my way back inside. I draped the sheet over the three chairs evenly placed beside the dining room table. It will hang there overnight, to shed the last of the dampness and to get warm and fully dry before it is ready to be folded.

I pinched the frozen clothespins to liberate the sheet from the line of rope that spans the back porch. The sheet was ice-cold; it’d been hanging outside on the porch all afternoon. I wrapped the yards of damp cotton over my shoulder, trying not to drag anything on the floor as I pulled the rest of the laundry – pillowcases and a few dishtowels – off the line and made my way back inside. I draped the sheet over the three chairs evenly placed beside the dining room table. It will hang there overnight, to shed the last of the dampness and to get warm and fully dry before it is ready to be folded.

This is a ritual that has been enacted in this house, on this porch and in this dining room, for more than fifty years. The tumble-dryer in the laundry room is not unused, but the sheets in this house have never seen the inside of it. No matter what season, my mother’s sheets are always line-dried.

“I need your help with the sheets,” my mother would say, a habitual plea generating the big eye roll from any one of her three children. This might be our Sisyphean task – second only to ironing my father’s handkerchiefs – a pesky chore we were commanded to do and our mother would not tolerate a half-hearted execution. We were guided step by step. “Put your finger in the dart. Pull it, tight. Stretch the sheet first. Flip it and fold. Now walk toward me…”

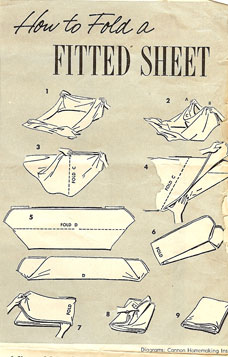

We found explicit sheet-folding instructions from a mid-twentieth century woman’s magazine, tucked in the back of some drawer. Was this how she learned her special way to fold fitted sheets? Or did she clip it because it matched the technique she’d acquired or invented herself? She would never say. But her systematic laundering and folding of sheets is part of our family lore.

Just picture the linen closet: towels on one shelf, sheets on the other – all squared, fluffed and folded, even towers of perfectly creased cotton. And when you go to make a bed – any bed in the house – the fitted bottom sheet opens itself for the bed, effortlessly, without a single wrinkle.

And the smell, the perfume of all the things that fly in the country air: cut grass, morning dew, apple blossoms in the orchard, summer rain, fecund grapes before the harvest, an icy winter storm. I need only to throw one of those freshly aired sheets over my shoulder or to slip myself into a just-made bed, to re-live my entire childhood with one inhale. Those sheets are an olfactory map of my earliest years.

During the last months of her life, when she was weakening, my mother’s friends admonished her to stop. She should save her energy. It was too easy to fall on the porch, too cold to be out hanging the sheets on the line. She should use the dryer. But my mother persisted. She has always preferred the feel and scent of her line-dried sheets.

This last week, my sister and brother and I washed her sheets every other day, taking turns pulling them from the washer and hanging them outside on the line and bringing them in to warm before folding. We all have the intuition – inherited, no doubt – about when they have been on the line long enough, or when, after hanging inside, they are ready to fold. One of us would call the other into the dining room and in tandem we’d lift the sheet and stand, facing each other, following the steps as though our mother was whispering them to us from the middle of her steady, uninterrupted slumber in the other room.

It is unspoken, but we all know why we’ve done this. This is still her house. We honor her with every load of laundry. Each time the nurse’s assistant came to give a sponge-bath and change the bed, we knew that my mother, even in a semi-conscious state, would be comforted by the familiar perfume of her porch-dried sheets. It was part of our vigil.

Then, this morning, my mother took her last breath.

My brother – her son, the doctor – checked her vital signs. I reached for my iPhone to note the official time of death. My sister wrapped her arms around me as I began to cry. We waited for a long stretch of time, watching to be sure that she would not take another breath, that this wasn’t just some irregularity, that this was the end. When we were certain, we kissed her goodbye, one at a time, and pulled up the sheet to cover her motionless  chest, a sheet that, once they came to take my mother’s body away, was washed and hung on the line to dry. A sheet that, tonight, before bed, we brought in and draped over the backs of the dining room chairs to get warm and fully dry. A sheet that, tomorrow, we will pull and stretch tight, folding it solemnly, like a prayer.

chest, a sheet that, once they came to take my mother’s body away, was washed and hung on the line to dry. A sheet that, tonight, before bed, we brought in and draped over the backs of the dining room chairs to get warm and fully dry. A sheet that, tomorrow, we will pull and stretch tight, folding it solemnly, like a prayer.