I’m typing away at my computer. It’s 3:45 in the afternoon and I’ve just hit my stride. The fits-and-starts of my own creative process now oiled and operating, I’m thinking crisply and spitting out maximum-words-per-minute.  It feels like I could cruise in this productive lane for hours, but for the hands of the clock, sweeping in on the witching hour. De-facto, best co-parent known to womankind, volunteers to fetch the kids at school. I’m grateful for an extra thirty minutes to profit from my momentum, falling back into my flow as soon has he’s out the door.

It feels like I could cruise in this productive lane for hours, but for the hands of the clock, sweeping in on the witching hour. De-facto, best co-parent known to womankind, volunteers to fetch the kids at school. I’m grateful for an extra thirty minutes to profit from my momentum, falling back into my flow as soon has he’s out the door.

Until I hear their cherubic voices in the stairwell. It should fill me with anticipation – if I were a good mom – but instead I feel dread. Here comes the hell storm of the evening grind. The door bursts open with the blast of post-school fatigue. Both girls, in high volume screams, run to me crying, each with her unique sob story. I have one too, but I know I’m supposed to swallow mine.

I wait without comment until the home-from-school-crisis fades, the screeching ceases and the tears dry. We agree to homework before dinner, which is when we discover that Buddy-roo’s new water bottle has leaked all over her cartable. Her schoolbooks are more than damp, her pencil case drenched, after sitting in the bottom of the bag with ¼-inch of water. I know I should be coolly pulling things out and laying them on a towel, but now I’m ticked off. It’s just another damn thing to do, another project for the evening that isn’t fun, restful or even interesting. It’s probably only fifteen minutes to lay out all her notebooks to air and blow-dry the interior of the bag, but there are a half-dozen other unexpected tasks just like this that result from being a mom to 8 and 10 year old girls, creatures old enough to be independent, but not at all autonomous.

I slam each of the books on the floor, not cursing with words but cursing with gestures. Short-pants slips around me and upstairs to avoid my mood. Buddy-roo has no choice but to witness it; she knows she can’t abandon me to dry out her schoolbag on my own. I turn toward the backsplash and breathe deeply, pursing my lips so I don’t utter a word that will be irretractable. I reach for a water glass to give purpose to this moment’s removal from the chaos of their presence in my life, and these few seconds taken to fill the glass and quench my angry thirst and calm me down so that I can be civil toward my offspring. I grab two towels, hand one to Buddy-roo, and we dry off the books as best we can, spreading them out, open to the air. We lay all the pens, erasers and other paraphernalia of her pencil case on another towel to dry overnight.

“Don’t be mad, mama,” she says, “I didn’t know the water bottle would leak all over.”

I’m not mad about the water bottle. I’m mad about the train wreck of my life every day after 4:30, and how I can’t manage my time better so that I’m poised and ready for them after school. Mad that I don’t have what it takes to be more compartmentalized, more together, more agile about the juggling act that is my life. I’m mad about the Sisyphean list of child-oriented household tasks, the laundry, the hang-up-your-clothes and wash-your-hands and do-your-homework-for-your-humorless-French-teacher and did-you-practice-your-viola grind, the acquisition of school supplies that have run out, the purchase of birthday presents for upcoming parties and the orchestrating of who-goes-where-and-how whenever De-facto and I are both out of town on the same days, the day-in-day-out-to-do-list that by the time they are in jammies and stories read and lights out, leaves me ready only to collapse into bed, falling asleep before even one page of my book is turned, wrung out from the last four hours of the day.

“I won’t be mad anymore,” I answer, assuring her with a gentler voice and my open arms, inviting her to an embrace. “Now we know not to use that water bottle in your school bag.”

She wraps her arms around me and squeezes. Is it a hug of appreciation, or relief? I really wish I hadn’t lost my temper; this gives me no leg to stand on when they start screeching. But what to do when everything you’re supposed to do, being on time, being conscientious, cheerful, responsible, reliable and all such hobgoblin behavior, is heavy on your shoulders when all you want to do is escape and run away, as far away as you can?

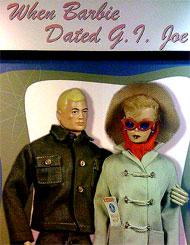

There is, for some, a point in a marriage where he buys a red sports car and has an affair, or she joins a book club or takes a pole-dancing class and has an affair. It’s the midway, midlife doldrums, when the grind of the day-to-day bears down one day too long, too hard, too much. The routine that was once cozily reassuring becomes relentlessly tiresome, compelling us to rebel and misbehave.

Is there such a point in parenting? A mid-parenting crisis? If there were, wouldn’t it settle in about now, halfway through their childhood, at age eight or ten with as many years left to go before the promise of an empty nest? The sleep-deprived diaper-changing infant and toddler years behind, you’d think it should be easier now. Supervision is still required, but at a diminished level from those formative years, which are as full-on as it gets but somehow that baby smell, the sweet odor emitted by newborns and small children, acts like a drug, seducing you to think that it’s really okay that your life has been turned totally upside down. The scent has worn off by now (replaced by the smell of lice shampoo) but the work is far from over. Even if you’re the best kind of limit-setting French-styled parent, it’s still a lot of work to keep up with your mid-childhood aged kids, no matter how well behaved they are.

I’ve had contact, very recently, with two of my college friends who have children in the midst of their junior-year-abroad. While remote mothering is still necessary, the relationships have shifted. They’re already speaking with pride about their nearly-adult children. I suspect, eventually, you turn some corner and you get to stand back and observe the success of your offspring, and relish the result of nearly two decades of parenting labor. Like you get to retire from intensive parenting and become a parent emeritus.

I’m in between the nascent parent and the at-the-finish-line parent. Halfway through the job of raising little souls, a balancing act between honoring their nature and enriching them by nurture, even though their nature’s starting to wear on me, the day-in-day out of dragging them out of bed and getting them out the door with the right coat on and their teeth brushed, and acting as PA with an entirely different schedule of pick-up-and-take-there every day of the week, all of this exacerbated by my attempts to continue to nourish myself and my own career. And I have an equal partner in parenting. I can’t even imagine the daily existence for parents with spouses who can’t or won’t help as much, or most of all, for the single-parents, moms or dads, who do it all without a sympathetic cohort.

It’s about now that I reach back and try to grab hold of the faded drama of our bleak hospital days, when Short-pants was in the ICU and we didn’t know if she’d reach her fourth birthday. I made no shortage of bargaining promises to any and all omniscient gods and higher powers who’d hear us, pleading against an unimaginable outcome that would remove her from our family and our lives. It feels petty to rail about being at the end of my rope in a mid-parenting crisis in light of that experience, a true and bonafide crisis. I know my current problems are little and luxurious. My children are healthy, creatively-tempered yet obedient-in-the-right-doses. They give abundant love, and all those gifts, expected and unexpected, that children deliver to their parents. I’m told, again and again, that it all goes by so fast and I should cherish these days, because soon I’ll long for them. But I know the days I’m longing for now, and they aren’t these.

A good friend likes to remind me that my children will be a comfort to me in my old age. But right now, I’m middle-aged and only midway through their childhood. It’s still my job to comfort them. I know this is a sob-story, my tiny mid-parenting crisis, but swallowing it hasn’t made it go away, and the idea taking up pole-dancing seems more appealing every day.