Advance to the Rear

There are times when life seems to take on its own momentum. Unlike the days where choice seems evident – debating the banal options of our routine lives, turn here or there, eat this or that – these are the eerily directed moments when events simply propel us forward and it feels that we have little say in any matter. My mother died and time hiccupped; seeming to pause momentarily as we stared at her still body, relieved for her, bereft for ourselves. Who do we call first? Let’s just wait a bit, take this in. We knew. It was a temporary stay of time, a last quiet moment before the rapid undertaking of after-death duties.

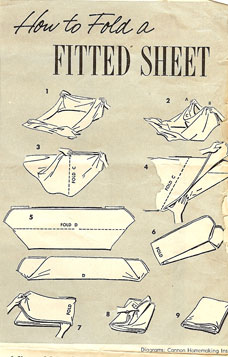

Once the call was made, however, a trigger was pulled and industrious activity ensued. The hospice nurse arrived and made an official pronouncement. The funeral director came, his head perpetually bowed. My mother wanted to donate the bones in her inner ears to science; this had to be orchestrated quickly, and on a weekend. Our immediate family was notified. Close friends were called. The obituary, previously drafted, required editing and (exhaustive) proofing. The laundering of sheets, the removal of the hospice furniture and putting my mother’s study back together. The calling of lawyers, reading of the will, signing of waivers, funeral arrangements, plane reservations for relatives flying in or not, depending on the inclement weather. The unfolding course of events urged us, relentlessly, onward.

Our mother was a woman who took much satisfaction from her own productivity. Even at the very end, she wanted a plan for the day. We are fallen apples, not far from that tree; our daily to-do list became suddenly daunting. The slow, quiet, waiting vigil of the aching days before her death gave way to a frenzy of tasks that were executed with an almost maniacal urgency while dodging the onslaught of casseroles and meat platters.

Looking in the mirror one tired morning, dark circles defining my eyes – the residue of a long vigil and stolen moments for private tears – I wondered exactly what fumes in my body were driving me forward.

Two weeks before my mother died, her sister sent her an email about a game they made up when they were kids, maybe 6 or 7 years old. They’d march around the back yard with sticks and curtain rods that they pretended were rifles and they’d shout out, “Advance to the rear!” My mother remembered the game; she instructed me to pull out her old photo album and she pointed to the picture of the house – the same house I saw in Havana – and showed me the route they followed, rifles in hand, out the side door and around to the back of the house. She said her father would get so frustrated with them; repeatedly explaining that it was not possible to advance to the rear.

But we were advancing, one step at a time, a last loving labor to finish what my mother had started by dying. Respects were paid; the ritualized calling hours sometimes awkward, often healing – the standing and greeting of her friends and admirers, the sharing of our grief. People came to console us but just as often we ended up consoling them. “Don’t be sorry she’s gone,” I told someone who would not stop crying, “just be grateful you knew her.” (But my sorrow remains, along with my gratitude.)

We put her in the ground beside my father, resting next to him the same way they used to sleep, side-by-side in their bed. We did this privately, without fanfare. Her friends and colleagues will be invited to a memorial service later, in the spring, when we will celebrate her life.

In retrospect, it was right to have this last private moment with her – with them. We stood there like kids stalling at the foot of our parents’ bed, saying an eternal goodnight.

We pressed ahead to finish the business of collecting important files and papers, cleaning out the refrigerator, coordinating with the caretaker who will stay with the house. We stood in the driveway to make our goodbyes, stunned by the list of sad errands we had completed in just one week’s time. I studied my sister and brother in the harsh winter sunlight. They looked tired, worn out – a reflection, no doubt, of how I looked and felt. Oh my god, I thought, she’s really gone. Oh my god, I thought, we’re old.

I’d phoned the airline nearly every day, searching for a return flight. With each call, I felt more like Dorothy asking anyone and everyone I came in contact with to please help me get home. I just wanted to get back home.

No amount of logic or emotion would solicit enough sympathy from a reservation agent to bend any rules. In the end, I  broke down and bought a new airline ticket to take me home to Short-pants and Buddy-roo and the heroic De-facto, Nobel-worthy after his 3-week stint as a single parent.

broke down and bought a new airline ticket to take me home to Short-pants and Buddy-roo and the heroic De-facto, Nobel-worthy after his 3-week stint as a single parent.

I would not have been able to accompany my mother this way had he not been so willing and agile.

Now I am home, back in the fold of my life. Back to my cherubs crawling in bed for the morning cuddle, the rush through breakfast and out the door to school. Back to my work and my clients and conference calls. Back to the bustle of a cosmopolitan city and the every-day routine of my regular world. Back to normal, except nothing feels normal anymore.

It was a campaign, these last weeks, to help my mother die, wanting her to die well, pushing myself forward to do what must be done, all the while missing my man and my little girls. It was a privilege to be there, to hold my mother’s hand and help her move through the last days of her life. It was a relief to come home to the hold-you-forever embrace of my vibrant little girls. And now that I have been there and back, I think I know exactly what it means to advance to the rear.