Looking Away

“Tell me again about the day Grammy died.” Buddy-roo had crawled into bed and was curled against me like a spoon. I was just falling back to sleep. Her words startled me out of that barely-there-light-doze.

What was it that prompted her, in that instant, to think about my mother? The picture I’ve been meaning to hang on the wall by my bed, the one of mom with a suitcase in hand on her way toward airport security – an iconic pose for her – is still tucked away on the jewelry shelf in my closet, waiting for the perfect frame to be procured. There’s nothing near my bed that would have conjured up her question. I wondered, but opted not to ask. Buddy-roo has the right to think of my mother whenever she pleases.

I repeated the story of that Sunday morning. How my mother was in a bed in her study, barely conscious for days; how her breathing had been irregular but then calmed; how I don’t remember saying this but my siblings tell me I told her the plan for the day is to let go (she was an organized woman who liked a good plan) and how we three sat with her, watching her, holding her hands, comforting her. And how during that one 45-second interval, for whatever reason – to use the bathroom, to fetch a sweater upstairs, to get some more coffee – we’d all left her unattended and she  chose that blink-of-an-eye moment to stop breathing. My sister returned, discovered her and called to us.

chose that blink-of-an-eye moment to stop breathing. My sister returned, discovered her and called to us.

(I think we are guilt-free about the fact that we weren’t right there at her side when she took her very last breath. We’d been there with her all weekend, in the way we were so often together as a family, in proximity but doing our own thing. None of us were surprised that she stole away while we’d been simultaneously distracted. I’d wager she was waiting for us to leave her alone so she could die in private.)

“But when did they come to get her?” Buddy-roo asked.

“Well, then we called the funeral director and he drove his big station wagon right up on the front lawn and came in to take her body away.”

“But when did they come to get her?”

“It was about an hour after she died.”

“No. When did she go?”

“Well, when she stopped breathing. I suppose that’s when she left.”

Buddy-roo deftly changed the subject, apparently satisfied enough with what she’d gleaned from my explanation. Then, as she does, she moved casually on to the next topic – a movie she wanted to watch, a breakfast request, a story from school. Conversation over.

Today my feet up in the air, against the wall, the cool-down position after a pilates session, breathing in and out as my trainer ran through a relaxation sequence. After whale-kicks with ankle-weights, ab-crunching contortions and dozens of humiliating lunge-squats, it doesn’t take much to enter a light meditation. The scene that came to me, in that state, is one that I see often in dreams about my mother. She is standing on the back porch in her summer robe as I walk from the driveway toward the house. Her body tilts slightly to one side, just like her mother’s did – just like mine will someday – and she is smiling, unconditionally happy to see me.

Then the tears came. They were good and I let them flow and my trainer understood. Later at home I told De-facto who held me while I sobbed against his chest, and he understood. Now in the quiet of my writing studio, I understand what I knew but pretended not to, how impossibly hard it is to grieve when you are busy. The recent respite from travel and work brings relief and rest, but panic as well; grief no longer compartmentalized into 10-minute cubbyholes grows heavy and damp around me.

I don’t know why it’s taken me so long to frame that photograph of my mother with her suitcase, the one I intend to hang by my bed. It is so her, she is on the move. I guess I learned this from her.

In my studio, on a low table just beside my desk, there is a collection of silver-framed photographs of my family: a portrait of my brother and his wife and children; my sister, sitting in front of the temple of Angkor Wat; my aunt dressed in a stunning red suit. They all smiled for the camera, which means that now they are smiling at me.

Two more photographs that stand on that table. In one, my father is barefoot at the beach. He’d been to a conference on the west coast, his first visit to the Pacific, evidently its call so enticing that he removed his socks and shoes and rolled up his suit-pants to feel the other ocean on his toes.

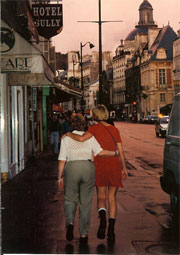

The other photograph is of my mother, with me. We are walking down the street with our arms around each other. It was taken during the first summer I lived in Paris, fifteen years ago when unbelievably I actually wore short baby-doll dresses with  black paratrooper boots. I remember that evening, walking beside her, headed toward a favored restaurant, mother and daughter together. I was sharing my Paris with her.

black paratrooper boots. I remember that evening, walking beside her, headed toward a favored restaurant, mother and daughter together. I was sharing my Paris with her.

Why, I wonder, have I chosen to keep and display pictures of my parents in which they are turned away from me? In both photographs, I noticed just today, they are facing the other direction, the back of their heads and their bodies the only reminder I have of them in this room otherwise filled with photographs of De-facto and my children and my family and friends – everyone else gazing straight at me.

Is it easier for me to look at them if they’re looking away?

My father, who’s been gone for over two decades, still appears in my dreams. I wake up happy, delighted for even a brief chance to visit with him in the dreamtime. My mother figures prominently in dreams these days, too, but I wake up sad, wanting more, feeling her absence. I am no stranger to grieving, I know that with time – our old friend time – the heaviness of losing her will dissipate and I’ll think of her without such a sorry weight. Someday I’ll wake up happy just to have seen her in a dream. But how long will that take?

Maybe that’s what Buddy-roo means. Maybe they haven’t come to get her yet – whoever they are, the ubiquitous they, the ones who work in tandem with time and help you let go of the people you love and hold near. When did she go, Buddy-roo? She hasn’t yet. Not until I let her go.