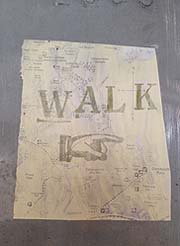

When you slow down, a window opens and you see things you couldn’t see before. When you take your time, you sense things, because you’re not rushing through life facing forward, you’re ambling along, receptive to what’s around you. When you give yourself time, you think things through, following a string of thoughts from one thing to the next and then further. Unlike the one-thing-to-another we experience while surfing the web or multi-tasking through a busy day, staccato and mercurial, the thought process that accompanies a long walk in the country is calming and fluid, like waves of water rolling forward and back and forward again.  It doesn’t take very long for the chatter to cease, the chirping in the back of your head quiets and the mind is filled with simpler thoughts. There is space for bigger thoughts, or the smaller thoughts have room around them to echo. You start to really see what’s inside you and around you, and notice things that you don’t notice when you’re in a rush.

It doesn’t take very long for the chatter to cease, the chirping in the back of your head quiets and the mind is filled with simpler thoughts. There is space for bigger thoughts, or the smaller thoughts have room around them to echo. You start to really see what’s inside you and around you, and notice things that you don’t notice when you’re in a rush.

~ ~ ~

Walking through Pamplona, one of the early stops along the Camino – this was in the beginning of May – I couldn’t help but be reminded of the rituals we enact there every July during the fiesta. It was odd to walk through that city without people and music spilling out into the streets. I walked down the empty Calle Merced, where in two months time, to the day, there’d be long tables set up end-to-end in the street, and friends would be assembling for a breakfast of greasy eggs and chorizo or pochas and red wine. I love those breakfasts, especially when the jota singers among the group stand up and sing their beautiful Navarran ballads. A man named Puchero is a force behind this, his voice bold and full, like his body. When he sings, his mouth stretches wide with each vibratoed note, his eyes bore into you, tearing sometimes because he is singing with such force. If he sings to you, the only thing to do is look right back at him with the biggest smile ever, and stay present to fully receive the song, sung in Spanish and if it is later translated, you are moved by the choice of words and their meaning.

For a minute, I wondered if the Fiesta Nazi, in a fit of generous mischief, would make some arrangement for Puchero to show up at my party and surprise me with a birthday jota. It would be only an hour’s drive for him, and not unthinkable for her to orchestrate something like this. At the same time, it was pretty far-fetched and highly unlikely. Still, I permitted my imagination to hold this image for a few minutes, just for the pleasure of the fantasy, picturing him singing to me and giving my assembled friends this taste of the Navarran culture. A little Walter Mitty moment during my walk.

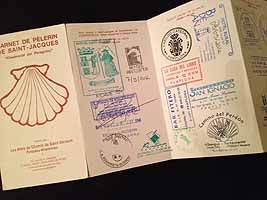

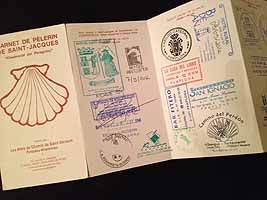

Two weeks later, when the pit crew kidnapped me to go to my party, I found myself back in Navarra. The day before the big celebration – on my actual birthday – we decided to drive by St. Jean Pied de Port to see where I’d started the Camino. My credentials were getting full – I collected stamps  not only from where I slept each night, but from the churches I visited and many of the cafe-bars I stopped at along the way – in St. Jean I could stop by the Camino office and get an extra pilgrim passport to use when my original one got filled up.

not only from where I slept each night, but from the churches I visited and many of the cafe-bars I stopped at along the way – in St. Jean I could stop by the Camino office and get an extra pilgrim passport to use when my original one got filled up.

It was lunchtime in France – only a few miles away, over the border in Spain, lunch was still something to look forward to – and we decided to eat in St. Jean, installing ourselves at a table on a restaurant terrace along the street. We’d barely clinked glasses when a squat, thick man charged up to our table, trailed by about a dozen other people.

“I know those two girls,” he said between a string of colorful curses. We knew him, too. It was Puchero. By chance, he happened to be visiting St. Jean Pied de Port with a group from Pamplona and just happened to walk down the street where we just happened to be seated. We were as surprised to see him as he was to see us. The Fiesta Nazi didn’t miss a beat. “It’s her birthday,” she said, pointing at me, “sing her a jota!”

Without hesitating even a second, he launched into song, his robust voice belting out a wailing call. His face right away red, the veins in his temple squeezed as he forced every cubic inch of air out of his lungs before a new breath and a new phrase. He literally stopped all activity on the street. Every passerby, every diner on the terrace, every waitress, every shopkeeper, craned their necks to watch and listen to Puchero as he sang me my birthday jota.

It was framed slightly differently than my fantasy of weeks before, but nonetheless, the same elements were there. But this had not been organized in advance, it happened by chance, that Puchero was there and we were too. Had I experienced some kind of premonition? Or had my little fantasy sent out a request that was answered? Or was it all just a coincidence?

~ ~ ~

The first time I had the dream was in Estella, five days into the Camino. I guess you could call it a pilgrim-stress dream, in which I walked to the next town only to realize I’d left my walking poles in the previous night’s hotel. I woke up, relieved to see those familiar bastóns leaning against the chair,  that I hadn’t left and walked an entire day’s stage without them. I had the dream again, the next night, waking to check that my poles were still there beside my bed.

that I hadn’t left and walked an entire day’s stage without them. I had the dream again, the next night, waking to check that my poles were still there beside my bed.

A few days later, I lingered in a room I’d shared with five others, letting them all finish their morning ablutions first so that I might have a more leisurely and private departure. (This was prior to the hot meseta after Burgos, when my timing changed and a just-at-dawn departure was required to make tracks before the midday sun.) On my way out, I set my poles against the table by the door, stopping to take advantage of the wifi signal in the lobby to send a word of love to De-facto before heading out for the day’s walk. The door closed behind me, and I walked three blocks before realizing I’d left my poles at the albergue. When I returned, the door was locked and when I knocked, nobody answered. I sat on the stoop wondering how long I’d have to wait to get my poles, when I remembered I’d called the proprietor the day before, his number was in my phone memory. A quick call and he was there in 5 minutes, unlocking the door so I could reach in and retrieve my walking sticks.

Hold on to those poles, I told myself.

~ ~ ~

He stood to the side of the path and beckoned to me, holding out a small bag. “Would you like an olive?” he said, “I just opened them.”

Always accept small gifts on the Camino, I’d been told. So I reached in and pulled one of the plump green olives from the package, trying not to put my sweaty fingers in the juice that preserved them.

“I’m Mark from Michigan,” he said. I hadn’t met that many Americans along the way, he reminded me how exuberant my countrymen can be. He thrust the small bag toward me again. “Have another olive.”

I’d been singing to myself all day, a kind of stream-of-consciousness name-that-tune, when one simple word could provoke an entire medley of songs. I took another olive, but held it in my hand while I sang to him one part of a song from Godspell, which includes the lyrics,Your wife is sighing, crying, and your olive tree is dying.

The song is actually a duet I used to sing, in spontaneous moments, with a good friend Dilts – we called each other by our last names as a form of endearment – his part fast and syncopated and my part slow and melodic. The last line of my part: When you go to heaven you’ll be blessed, oh yes, it’s all for the best.

Mark from Michigan looked me straight in the eye, just the way I’d looked at Puchero when he sang to me, for the entire song, which I did not rush through, but rather sang to him very deliberately, emphasizing especially the word olive, to nod my head at the cause for this melody.

“That’s beautiful,” he said, when I finished. “If I go to heaven, I’ll wait for you there.” I ate my olive, thanked him again, and walked on.

Singing that song had conjured up images of my friend Dilts, his wry smile and his dry wit. He died eight years ago, cancer took him before he could turn fifty. I carried him with me for several kilometers, vacillating between missing him fiercely but also laughing out loud at things I remember him saying and doing. A lasting image of him, still in my mind now: his smart-ass smile, one eyebrow raised and jubilant fist in the air. I had Mark from Michigan to thank for conjuring up that string of memories, all from one single olive.

~ ~ ~

I made it to León, after 20 days of walking, covering 450 kilometers. The very last leg, by bus, as I didn’t want the lingering memory of this stretch of the Camino to be the industrial suburbs of the city. I figure the day I walked  on the Camino Baztanés from Urdax to Elizondo is like extra credit, and makes up for the sage decision to avoid the plight of an urban pilgrim. A friend, an avid hiker, had joined me for these last two days of walking. Even she agreed this was a better choice than to march through truck fumes and under highway on-ramps. I could see much of the Camino route from the window, so I followed the trail with my heart, even though my feet were on the bus.

on the Camino Baztanés from Urdax to Elizondo is like extra credit, and makes up for the sage decision to avoid the plight of an urban pilgrim. A friend, an avid hiker, had joined me for these last two days of walking. Even she agreed this was a better choice than to march through truck fumes and under highway on-ramps. I could see much of the Camino route from the window, so I followed the trail with my heart, even though my feet were on the bus.

We took a train from León to San Sebastian, and in the rush of getting off the train, I neglected to pick up my poles, which I’d meant to strap to my backpack, but hadn’t gotten around to it, as they were useful until the last moment getting on the train. I’d put them on the overhead shelf and when I pulled down my pack, I somehow didn’t think to grab them. In fact, I didn’t realize they were missing until we’d walked ten blocks through San Sebastian in search of our hotel.

I didn’t get upset, even though they’d carried me so many miles, even though they’d become an extension of my arms, and probably a savior of my back, even though I loved the little feet I’d bought to cover the noisy metal tips. I let them go. Not that I gave up: once we checked into the hotel, the proprietor was very happy to help me call the RENFE and register the loss in their records, just in case. The next day I visited the lost and found at the terminus, the same station where we’d board our train to Paris. There was no sign of them. They are in someone else’s hands now, but hopefully helping them to walk as well as they guided me.

I wasn’t paying attention. That’s when you miss things. But hadn’t I seen that coming?

~ ~ ~

Word passes on the Camino without texts or emails. The weaving that happens as you walk puts you in touch with different people over the course of a day. You might walk with someone for fifteen minutes and then pull ahead, only to run into them again a few hours later when you’d stopped for a rest at a village cafe. Or someone you hadn’t seen for days would somehow get in step with you again. In the meantime, they’ve walked and talked with others, and if there is news to share, it gets passed along. After Burgos, there was a rumor about someone who’d gone to sleep in the albergue there and hadn’t woken up. This wasn’t the first death I’d heard about during my walk: a 65-year old man had a heart attack on his very first day, going over the Pyrenees. The story told was his wife had died the year before, his Camino was meant to help him sort through it. Nobody I spoke with felt too terrible about it. “Perhaps he’d joined her,” they said, or “it’s not a bad way to go, walking the Camino.”

The amazing night I stayed in the Ermita de San Nicolas, after our feet were washed and our dinner was finished, my friend from Romania turned to me and asked if I’d heard about the man who died in Burgos. “You knew him,” she said, “I saw you talking to him.” She described him, but I couldn’t place him. She kept saying his name, but it didn’t register. “Yes, you knew him,” she insisted, “Mark, Mark from Michigan.”

I fell silent then, thinking about the lyrics in the song I’d sung to him, remembering our very brief exchange. Did I see that coming? Was it just another coincidence? That day, the day I shared his olives, I must have been paying attention to something.

If there is a heaven – and I’m not always sure of it – but if there is, I hope he’s there. I hope he’s met up with Dilts, who can sing him the other half of the duet. And if he is waiting for me there, well, I hope he knows I’m not in a rush.

until this summer, when the noise from the glis-glis proved too much for them – and offered a sultry hand.

until this summer, when the noise from the glis-glis proved too much for them – and offered a sultry hand.