Empty Rooms

The movers from the Second Hand Shop descended upon my mother’s house, infiltrating each room with boxes and newspapers and packing plastic. The women quickly set to picking up the little pieces of my mother’s past: the small bowls and ashtrays and decorative items that had been once carefully placed on end tables, coffee tables and the shelves of her secretary, the bookends and clocks and other decorative items stripped from the shelves of those tall rooms. My siblings and I took the things that had sentimental value to us, but we left even more behind; none of us have the room nor do our homes have the same décor to receive the bounty of my mother’s good taste.

I watched them wrap each piece in paper, all the little dishes and coasters, her translucent Belleek vases, the small ceramic plate from their trip to Greece, the leather-covered decanter we always imagined had a genie living inside it. I knew and appreciated the stories of all these objects, yet none were compelling enough to inspire putting them in my shipment to Paris. Still, I was sad to see the lovely things all taken away.

They wrapped the odd sets of china that none of us could fit on our own cabinets, and then the silver serving dishes. I had to turn away when one of the women wrapped the dome-topped silver casserole, the one that usually housed the green beans at Thanksgiving. How many holiday meals it was a fixture on her table among the other platters and bowls dedicated to the meat or the mashed potatoes or the long silver tray with its linen liner that folded up and wrapped the just-out-of-the-oven parker house rolls. I don’t set such a formal table – few people do these days – I would use this serving dish only once a year, if at all. Plus I have no place to store it. So it goes away, hopefully to add elegance to someone else’s holiday table.

In the meantime, the men grunted down the long central staircase carrying beds and bureaus and long heavy mirrors. We’d each taken a few favorite pieces of furniture, but so much was left, all that had been acquired over the years to fill the thirteen rooms. Some of it ended up in friendly homes: the dining room set is already in the house of one of my mother’s colleagues, a photograph sent to  us to show its placement. That other people are gathered around that table gives me immense pleasure, though now I wish we’d thrown in the casserole server; it was so at home on that table.

us to show its placement. That other people are gathered around that table gives me immense pleasure, though now I wish we’d thrown in the casserole server; it was so at home on that table.

The wrapping and packing and hauling was intense for several hours. In the midst of it, my movers came to collect my boxes from the basement. Nineteen years ago when I left the states to adventure in Europe, my mother supported this dream of mine by building shelves and laying cement on what had been a dirt floor in the cellar, so I could store my possessions for the few years I expected to live abroad. Though I culled those boxes down about five years ago, there were still a dozen left and some furniture I’d loved too much to sell. There were also a few things from my mother and both grandmothers that I chose to send across the ocean. And the Fisher-Price toys: for months after my mother died, Buddy-roo harangued me, “what are you going to do with all those toys?” I’ve decided what the hell, I’m shipping them. They’re on their way to France.

~ ~ ~

I embraced my brother goodbye a second time (he made it halfway to the car before turning back for another hug) and after he drove off, I stood on the porch and thought about how my mother must have felt each time we left her standing there. Did she feel as empty as I did now? Or was she happy to see us go? (Maybe a bit of both.)

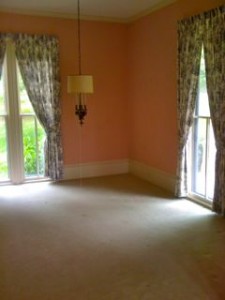

Inside I toured each room of the now empty house. The echoes of everything that ever happened there filled the vacant rooms. I could picture each room in all its iterations over the years. This one once painted pale blue, with a white piano and a picture of our house, painted by my grandmother, hanging on the wall. The Christmas tree went in the corner. Later the room was painted light green and carpeted in the same color. The day that they laid that carpet, the room was empty just as it was now, and I rolled back and forth from one end of the room to the other until I was too dizzy to stand up. My mother scolded my brother and sister for writing their names, with their fingers, in the fresh pile of the carpet. My father came home and showed them a better way to do this, with a yardstick, and he, too was admonished.

There, on the floor by the front screen door, as it rained a gentle summer shower outside, I remember listening to the newly released Sgt. Pepper’s album and reading the liner notes. Or taking over the two front rooms and setting up all the Fisher Price toys and playing with them all day (and decades later, watching my children do the same thing). The card table was placed under a lamp in which my father would hide a puzzle piece before offering a prize to the person who put in the last piece. In that corner over there, the newfangled 8-track player had been placed on its custom-made stand, with Billy Joel’s The Stranger playing on it while mom and I trimmed the Christmas tree. She’d coach me to hang the bigger balls on the bottom and the smaller ornaments on top. She couldn’t help but correct my improper placement and I suffer this compulsion, too, with my own daughters.

In each room a hundred stories could be told, and in this empty condition they all screamed at me at once, or in succession: mom and dad’s cocktail parties, the Christmas mornings, the “talks” after I’d misbehaved at school, the impromptu parties when my parents were out of town, the family celebrations, the quiet Sunday afternoons. All of it: the happiest moments of my life, and probably some of the saddest, too, dancing and circling around me in the empty rooms of my childhood home.

~ ~ ~

I walked through the airport like a zombie, shell-shocked from the emotions dispensed these last days. On that last morning, a final tour through the empty house with an out-loud thank you, heartfelt, to each room for the stories it yielded and for the protection given to me and my family for so many years. I paid special attention to my hand on the doorknob, closing the back  door for the last time, locking myself out, the key inside in a box in a drawer, left for the next owners. I slid my hand down to the bottom of the door, pressing my fingers into the grooves carved there by our old woodchuck hound. For all his fourteen years, he scratched his paws against the door to let us know he wanted to come in or go out. Long after he’d died, my parents renovated the house but opted not to repair or replace the doors, leaving his nail-marks embedded there, keeping his memory in the house. I scratched at the door, just where he used to, not really wanting to go back in, but not wanting to stay out, either.

door for the last time, locking myself out, the key inside in a box in a drawer, left for the next owners. I slid my hand down to the bottom of the door, pressing my fingers into the grooves carved there by our old woodchuck hound. For all his fourteen years, he scratched his paws against the door to let us know he wanted to come in or go out. Long after he’d died, my parents renovated the house but opted not to repair or replace the doors, leaving his nail-marks embedded there, keeping his memory in the house. I scratched at the door, just where he used to, not really wanting to go back in, but not wanting to stay out, either.

October 3rd, 2011 at 3:22 pm

Life sure is a test sometimes…cherish every memory as I know you will….and have shared so beautifully with all of us. Safe travels and love,

Betty

October 3rd, 2011 at 4:49 pm

Wow. Touching beyond all bearing. It occurs to me that your life circumstances– the one house, always– are extraordinary among your generational cohorts. Many of us moved once or twice (or more) as kids; and many of us, further, watched our parents, either together or singly, move from one of our childhood houses some time later. We had our moments of memory and poignancy, and maybe more than one of them, but in dealing with smaller expanses of time I’m sure these were nothing compared to what gets stored up in a family’s consciousness, its energy system, when you’ve had only and ever the One House. I don’t know how you weren’t simply knocked over into a puddle of tears, over and over.

October 4th, 2011 at 1:54 am

But I was in a puddle of tears, Jeremy. over and over again. (and thanks for your lovely comment)

October 4th, 2011 at 2:09 am

I read this tears streaming down my face…like letting open the flood gates that have kept back my own emotions of cleaning out and selling my childhood home after my mother’s diagnosis of dementia. I have tucked all my feelings neatly away…with excuse it was best for my son…or my job…or even my mom…thank you…thank you for the catharsis. Long overdue!

October 7th, 2011 at 1:16 am

My folks lived in the same home for 36 years. In 2001, they moved one block down the street. I moved out when I was eighteen, to go to college. I returned home for those four summers, and then only for whatever holidays that followed, that I could. Still, for fourteen years, going home meant only one thing, traveling there.

When they moved, I came and stayed with them. My sibs, lived nearby and returned home at the end of each day of packing and moving. On our last night there, my son and I slept in sleeping bags in my old, and now empty, room. My parents new house was not yet home for me. I wanted to hold onto the only one I’d ever known, for as long as I could.

My son was four at the time. Part of what I hoped for from that trip, was to pass a sense of the specialness of my childhood home, to him. Midway through the evening, I heard the front door unlock, followed by laughter. I arose to see who could be coming in. It was the daughters of the new owner. They knew my folks had moved out that afternoon. While their dad didn’t take possession until the following morning, they had keys and were hoping to spend a first night in their new home.

We talked awkwardly for a few moments. I welcomed them and wished them much happiness. They left and wished me one last good night of sleep. I too, walked through each room before we left, and said goodbye. I took pictures too. When I look at them now, it’s a strange experience. The rooms in the pictures are are empty. Yet when I think of them, they’re full of furniture and decoration and people.

Today, when we make the trip to North Jersey, my son recognizes the house. My daughter does too (even though she’s never set foot inside). I never did see the girls again. My mother’s visited with the new owners and tells me they love their house. I find home now, both where I live, and in the places where people I love live. That includes the place down the street from my childhood home. Each too, holds in memory, my version of your “dome-topped silver casserole.”