So We’ll Never Forget

I have always been the documenter of our family’s history. As a child I would stack together multiple pages of paper, folding and cutting them to create pocket-sized books. I’d write about our family rituals or offer how-to advice. These books were a source of great entertainment to my family and good fodder for teasing me, still, to this day.

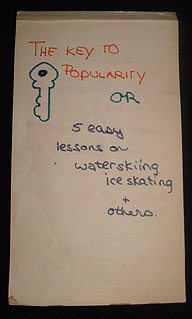

My most famous title, The U.D.T. Rool Book, a palm-sized field guide I wrote when I was 7-years old, described, step-by-step, our family’s summertime swim-in-the-lake ritual, as practiced by the Underwater Demolition Team (U.D.T.), a club invented by my father to get us out of bed and in the lake every July morning. Another family favorite: the handy pamphlet titled The Key to Popularity, my very first (circa 4th grade) effort at parody, a tongue-in-cheek embellishment of my mother’s theory that if she just made sure we all learned how to ice-skate and water-ski, we’d be popular.

The Key to Popularity, my very first (circa 4th grade) effort at parody, a tongue-in-cheek embellishment of my mother’s theory that if she just made sure we all learned how to ice-skate and water-ski, we’d be popular.

As happens with the artifacts of our childhood, these little books disappeared. And then, during renovations or severe spring cleanings, they re-appeared. When my mother recovered The Key to Popularity, probably in the back of some drawer, she put it in its rightful place on the kitchen counter, in that the space that is a magnet for all manner of junk – those old, chewed-on, unsharpened pencils, pens that no longer work, worn nail files, remnants of note pads, tchotchkes and campaign buttons – the miscellaneous counter in our kitchen (we all have one, don’t we?) where things just end up and somehow, stay there.

Every time I went to visit my mother, The Key to Popularity was still there, wedged in a square lucite box meant for Post-it notes that were used up over a decade ago. This little book, like many of the masterpieces I authored as a child, was a charming chapter of our family jokelore; she couldn’t bring herself to throw it out. But I cringed every time I saw it.

When my father died – twenty years ago – at the age of 59, we assembled in shock, unprepared and unbelieving. Things we’d meant to say had gone unspoken. Nothing so dramatic that he didn’t probably know already, but still, it felt as though he was plucked away from us; his life was interrupted. The painter who made a portrait of him, later, purposefully didn’t finish the canvas, in homage to his unfinished life.

On the day we buried him, prior to the mass, there was a small private service at the funeral home, the last viewing of his body before the casket was closed. We stood around him, shedding tears – and giggling. “What are you all chuckling about?” my mother asked, mildly perturbed as she approached us at the casket. She saw the little trinkets and photographs we’d placed beside him and she smiled. When I showed her The U.D.T. Rool Book tucked in the breast pocket of his blazer, she took my hand and squeezed it. She even chuckled with us when she saw what had been slipped under my father’s lifeless arm: the previous Sunday’s New York Times crossword puzzle and a sharpened #2 pencil. “You kids,” she said.

How many times I heard her say that: You kids.

But the truth must come out: It was my mother who started the tradition of doing the Sunday Times crossword when my parents were dating in college. She was, by her own report, quite skilled at crosswords – more adept than my father. But she figured out quickly that if she didn’t answer all the clues she knew right away, it would take longer to finish the puzzle, elongating their afternoon date. This was a surprise to me; I’d always associated my Dad with the Sunday crossword. I asked her about this and she shrugged. “He got so good at working the puzzle, I let him take it over.”

My mother told us, knowing it was futile, not to put anything in her coffin with her. I teased her that I would bury her with the family carrot, but in the end I had a better idea. I tucked The Key To Popularity in beside her, next to the white satin interior of her casket, just a little helpful guidance for heavenly social interaction.

There was something else lying around on that kitchen counter: a hand-made origami oracle that Short-pants gave to my mother last year, to “help her with important decisions.” Constructed out of intricately folded paper, this device resembles an egg carton in which you insert your thumb and index finger and move the triangled peaks this way and that way. With a ritualized guess of numbers and colors, the correct answer to all-important questions can be divined, much like the famous 8-ball, with oracle-like responses under the folded flaps: Yes, of course or Maybe not.

Though I was not present during the days that my mother made her decision to stop treatment and enter hospice care, I have this fantasy that she stood, leaning against her kitchen island, moving her fingers back and forth within the folded paper, asking the question, “Is it time to go?” and that Short-pants’ oracle gave her the response that settled it once and for all.

This folded contraption was also placed in the casket with my mother, in case she needs to make any decisions in the afterlife.

My mother’s mother, my Grammy, used to tell us that she and Grandpa had a plan to meet up after death at the entrance to Macy’s on 34th street in New York. When she died, I imagined some purgatorial dimension where their fantasy was lived out, returning to the roaring twenties that belonged to them when they were roaring, in their twenties, and finding each other again.

So I imagine my mother, holding her edition of The Key to Popularity, meeting up with my father, with the original U.D.T. Rool Book in hand, comparing notes about the memories of their happy life together. “Sure glad she wrote it all down,” they’ll say, marveling at my little handbooks, “so we’ll never forget.”

And then Daddy will pull out his copy of the New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle, and they’ll work it together, for eternity.

February 21st, 2010 at 9:33 pm

My daughter is in the process of creating so many of these little books of stories and guidelines. I stash them all away, knowing that one day she will pick them up and look at them as if they were a gift.

Hope that you are back into your daily life and enjoying the comforts of its rituals.

February 21st, 2010 at 9:47 pm

you really have a talent for writing. an obvious thing to say. but you do. It is a blessing I hope for you to have this ability to transform your feelings into words.

February 22nd, 2010 at 10:49 am

These words are invaluable! Your sense of life and what is important so grounded in these exquisite details. The people become so unique as they all are.

February 22nd, 2010 at 4:09 pm

I love this. So much. So completely perfect. And, I dare say, it’s partially because I feel so many touchpoints, similarities. We have the family wig – just one – but it’s the kind of perennial your carrot is. And now we have an itinerant coconut, which began its travels in 2001, and is pausing with my youngest nephew, regaining strength for its next appearance.

You did well by your parents, as they did by you.

February 23rd, 2010 at 2:50 pm

These posts just keep getting better and better…

February 23rd, 2010 at 7:49 pm

Ditto to all of the above. Plus, I always wondered how one spelled tchotchkes!

February 23rd, 2010 at 8:55 pm

You have a real gift and are an inspiration to me.

PS: We will miss you at the Pamplona party in Fort Lauderdale. Is that a non-sequitor? Tom