This could be just another case of the Emperors new clothes, I told myself, riding up the escalator to see an art exhibit about nothing. De-facto took the girls to the Centre Pompidou to see it at last weekend –- a gesture to give me a few hours of coveted quiet. They returned from the museum, boisterous and enthusiastic. “There were big, empty rooms, and we ran all around,” said Buddy-roo. I gave De-facto a scratching-my-head look. “Go see it,” he said.

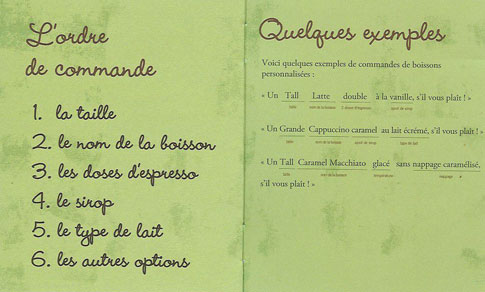

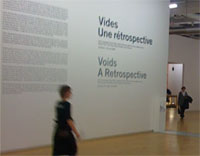

“Nothing seems to me to be the most potent thing in the world.” This quote from Robert Barry, an artist featured in the exhibit, “Voids. A Retrospective.” He’s one of nine “radical” artists so fascinated with nothing that they all created exhibitions made up of completely empty spaces.

The exhibit is just that: nine consecutive empty rooms. In the corridor, large panels of text describe the story of each artist’s dance with nothing. My favorite was Laurie Parsons, who in 1990 decided not to present anything for her third solo exhibition. She sent out invitations with the gallery address, but without her name or the date of the show. Eventually, she even deleted this show from her resumé, nearly erasing any trace of its existence. To respect her intentions, the exhibit literature reads, “the room devoted to her exhibition has no label.”

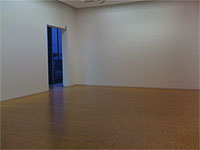

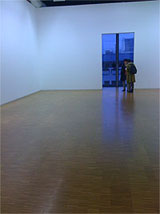

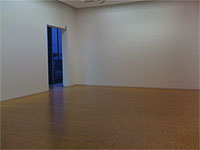

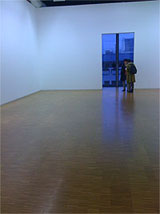

Because there is nothing to absorb the sound, a room with nothing in it is filled with a great quantity of noise. My footsteps echoed brightly against the empty walls. A row of spotlights hanging from the ceiling pointed at nothing along each wall. Without paintings or fixtures to absorb or deflect the light, it was almost blinding. I noticed, for the first time -– and I’m no stranger to this museum — the raw pattern of the parquet floors. Without anything in it, I saw the room for real: small imperfections in the walls, scuff marks on the floor, a lonely wire hanging from the ceiling.

along each wall. Without paintings or fixtures to absorb or deflect the light, it was almost blinding. I noticed, for the first time -– and I’m no stranger to this museum — the raw pattern of the parquet floors. Without anything in it, I saw the room for real: small imperfections in the walls, scuff marks on the floor, a lonely wire hanging from the ceiling.

I looked around at all the nothing. And then, something came to me.

A memory of another room –- an almost empty one -– in a building I once inhabited a long time ago, a renovated schoolhouse with long windows and cathedral ceilings. The rooms of the apartment were open to each other and filled with light. I remember just days after moving in, the man I lived with surprised me with a silver ten-speed bicycle for my birthday. We had only a few pieces of furniture, a handmade Shaker table, sideboard and a desk. I jumped on the bike right away and rode it around inside the apartment, a thin imprint from the tires marking a trail in the new carpet. When he wasn’t looking I took off all my clothes and rode the bicycle around in a circle again, in the nude, just to make him laugh. I remember how when he saw me, his head fell back and bounced upright again with a wide smile.

Well there’s a memory that came out of nowhere.

Whenever I walk through a museum, a blanket of quiet concentration wraps around me. As my eye is drawn to each work of art, the clutter of the day-to-day recedes from view, and a calm, focused state of mind sets in. It’s

like drinking a dose of culture, a thick and nourishing, aesthetic milkshake.

like drinking a dose of culture, a thick and nourishing, aesthetic milkshake.

I found myself again in that art-altered state, but it was different. With nothing on the walls or in the empty room to draw my attention, my attention turned inward, to my own things, to my own empty.

The four bare walls in the next room stared me down, and even though they were of the same chalky white plaster as the first room, and the wood was the same strip-floor pattern, this empty room was different.

I thought about joining the empty room with my empty head. But I could not — as someone more disciplined at meditation would — turn away all the images that came to me. They seemed too precious, little gifts presented to me in empty boxes. Like the one I gave to my sister, when I was old enough to think of giving her a present for her birthday, but too young to have the means to purchase anything. I rummaged through the store of boxes my mother had stacked in the back room and found a small, square, white box with a thin bed of white cotton inside. I wrapped the box. My sister opened it, guessing, probably, as she tugged at the ribbon, that it was empty. How she marveled at the imaginary item, treating it as though it was the most treasured gift she’d ever received.

Given the excess of this decade, fueled by the shallow economy of obsolescence and the coercive vanity-inducing power of the media, an art exhibit about nothing feels like a vacation from the obligations of consumerism. Without the clutter of things, there is room to think, or room to unthink. And room to remember. There is room to count what matters. There is an unburdening.

Robert Barry described nothing as a way to be “free for a moment to think about what we are going to do.”

Another one of the empty rooms reminded me of a moment last summer. We’d cleared out our apartment – no small task with two small children – to re-plaster and re-paint after a particularly grueling roof repair that had lasted too long and damaged the ceiling in every room. When the painters were finally done, De-facto and I laid on the floor of our empty living room, holding hands and staring up at the pristine ceiling while the children ran around us in wide, noisy circles. Only the largest pieces of furniture remained in the room, draped in plastic. All the carpets had been rolled up and the little side-tables and child-sized chairs had been evacuated. An entire wall of shelves had been cleared out, all the books and pictures and objets d’art packed away in brown cardboard boxes. I felt no urgency to move the furniture back, or to unpack those cartons and restore the room to its cluttered, lived-in state. I liked its new wide-openness.

Later, two friends happened by, in the neighborhood taking their fresh new baby for a walk. We got the idea to call our friends Lucy and Ricky from downstairs, and an impromptu pasta dinner party ensued. I remember sitting at that festive table –- set up smack in the center of what was an otherwise empty room -– watching my children and listening to my friends. I remember wondering if I had the courage to never unpack those boxes, if I could just leave them and let the room rest. Empty of all the objects that I’ve acquired, there’d be nothing to distract me from what is most essential: family, friends, food and wine. Nothing beats that.

water for splashing on your face. They’d finished dinner, but saved plates for weary travelers (my mother-in-love returned with me). Another bottle was opened. My temperature descended. The banter and laughter around the table worked its magic. The wine helped too. By the time our friends left, I was too tired to care.

water for splashing on your face. They’d finished dinner, but saved plates for weary travelers (my mother-in-love returned with me). Another bottle was opened. My temperature descended. The banter and laughter around the table worked its magic. The wine helped too. By the time our friends left, I was too tired to care.