Just a Minute

It happens unfortunately rather often these days, a lone gunman goes postal, sending a battery of bullets into a crowd full of innocent people. It’s horrible; a dreaded disbelief grips me when I hear this kind of news. There’s an extra groan when it happens at a school or involves small children. Then there’s proximity, when it’s closer to home it’s a real wake up call. Bad things can and do happen. It could have happened right next door.

On Monday De-facto made lunch and turned on the television – his ritual moment for absorbing local news – and we learned of the fatal shooting of four people, including three students, at a Jewish school in Toulouse.

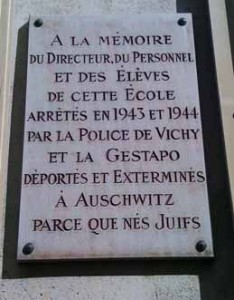

Given that we live in one of the Jewish sections of Paris, it’s easy for me to imagine this happening. Almost every school in our neighborhood has a  plaque posted near the door, often adorned with flowers and tri-color ribbons, commemorating the young students who were deported to the Nazi concentration camps. The maternelle school just behind our apartment building, where Short-pants and Buddy-roo both started, is often selected to host the somber ceremonies of remembrance for government dignitaries. The school our children attend now has a Catholic flavor – though in typical French style you can opt out of the religion part – but I could imagine them being at the wrong place and the wrong time here in our very own neighborhood and being caught in the crossfire.

plaque posted near the door, often adorned with flowers and tri-color ribbons, commemorating the young students who were deported to the Nazi concentration camps. The maternelle school just behind our apartment building, where Short-pants and Buddy-roo both started, is often selected to host the somber ceremonies of remembrance for government dignitaries. The school our children attend now has a Catholic flavor – though in typical French style you can opt out of the religion part – but I could imagine them being at the wrong place and the wrong time here in our very own neighborhood and being caught in the crossfire.

We didn’t mention anything to the girls. That wasn’t a deliberate decision. De-facto left for a business trip shortly after lunch that day, and I was busy preparing to leave for my own voyage d’affaires the next morning. I still had to prepare my valise, and with De-facto already gone it also meant attempting to get Buddy-roo ahead on her homework, leaving notes for babysitters and organizing the next day’s wardrobe and backpacks for an early-morning-drop-off at a neighbor’s house so I could make a train that left Paris before school started. In the flurry of activity, I didn’t bring it up.

In my hotel room on Tuesday night, I read and watched the news, with poignant images of the vigil in Paris and mention of a minute of silence in the schools across France. I was only in Luxembourg, a short trip on a fast train, but all this made me feel too far away. I do appreciate the break from my children, except when something happens that makes you want – need – to put your hands on them and hold them close.

Last night I dropped my small suitcase – my mother’s old little rollaway gets a lot of use – in the foyer and was rewarded with the stampede of bare, just-bathed feet down the stairs and young girls pummeling themselves against me. That welcome home hug is worth every travel hassle you have to endure, and it felt especially comforting this time.

I beckoned them to sit on the couch with me, one on each side, and I turned back and forth, asking about the two days of their lives I missed – how the geography test went (Buddy-roo had to map out the mountain ranges of France), how was the spelling coming (Short-pants has nearly memorized 12 pages of spelling words), and then my big question.

“Did you have a minute of silence at school?”

Lots of nodding yes.

“Did they tell you what it was for?”

Lots of nodding no. Then the two of them talking at me at the same time with different stories. After settling the debate about who would go first, here’s what I learned: One teacher simply said that this was something being observed at all the schools in France, so Short-pants had no idea she why she was participating in a minute of silence. Though Buddy-roo’s teacher referred to the event in Toulouse, it was obvious that she still didn’t really understand what had happened. One of her classmates was cited as a source of additional information; you can imagine the facts were jumbled, though reported to me with enthusiastic certainty.

I don’t want to conjure up unnecessary fear in their young minds about a lack of security at school or in the neighborhood. I don’t want to impose the weight of a terrorist act on them. To speak to children of such atrocities feels unfair, like I’m robbing them too soon of their innocence, tarnishing their sheer belief in the goodness of people and the world. But to shield them from what happened seems equally unfair, especially if it means they hear snippets from someone else, someone ill-informed or ill-equipped to inform them with the age-appropriate sensitivity.

I asked them if they wanted to know the reason that there was a minute of silence in school the day before. They’ve said no to questions like this before, for instance when I was explaining the birds and bees to Short-pants and at some point I said, “Is this enough, or do you want to know more?” With just a few seconds of reflection she said, “That’s enough for now. You can tell me more later.”

They did want to know why, so I told them about how a really crazy guy, someone not right in the head, had taken out a gun and shot at the people in front of a school, how the moment of silence was to honor the four people who were killed, to think of their families who were grieving. Of course I was bombarded with whys, and I did my best to explain in simple terms the idiocy of religious and racial violence.

“But it’s all the same God,” said Short-pants, “what does it matter?”

Then a barrage of questions about guns. “Why do people have guns? Why were guns even invented? Why would someone take a gun to a school, and shoot children?”

I couldn’t come up with a good answer, at least not one I believed myself. “That’s another reason to have a minute of silence,” I told her, “so that maybe people will ask themselves just those kinds of questions.”

This morning after dropping the girls off at school, I stopped at the nearby café where parents who don’t have to rush to work gather every morning and catch up over coffee. I brought up the minute of silence, which met with mixed reactions about how the school and the teachers had handled it. One parent referenced interviews with French psychologists saying that there’s no reason to burden young children with this news event. But how can you avoid the inevitability that they’ll hear about it and be terrorized more by what they don’t know than by what they do know?

For a minute, I wondered if I did the right thing, explaining it to the girls? I guess I made a choice to respect my kids rather than protect them. There’s probably no single right answer to that question. I just wish it was one we didn’t have to ask.

March 22nd, 2012 at 9:24 pm

I agree with your choice. To not mention it creates a dual world where certain things they will surely find out about elsewhere are not mentioned at home.

March 22nd, 2012 at 9:29 pm

It was a tragic event and it is so sad that events like this begin to rob our children of their innocence and carefree childhood, but sadly its life. Your blog reminded me of when my girls were at school and the way the school handled the Dunblane Massacre . Several of parents felt it was wrong that the school mentioned it all- but I disagree – it was in the press, on the television (in fact BBC childrens television had a news programme and handled it brilliantly)and the topic of conversation. I think its much better to confront the issue and talk about it openly and transparently.

March 22nd, 2012 at 9:37 pm

In the States after 9/11, you couldn’t avoid the images of planes crashing into the World Trade Center. They were ubiquitous. I was in Pittsburgh, and my son was with his mother in Atlanta. He was four. I don’t remember what we told him. What I remember is that for several months after, he built towers of legos and knocked them down. He was working it out.

This morning, I stumbled across this series of photographs, contrasting post-tsunami views in Japan with the same ones today: http://www.boston.com/bigpicture/2012/03/japan_tsunami_pictures_before.html. When the tsunami hit, I watched some of the videos that were uploaded to YouTube with my son and daughter.

My son is fourteen now. His sister is nine. He was stunned. She had the interesting questions. “Daddy, how could the water lift up a truck? Trucks are heavy.” I did my best with the physics of it.

Five months later, heavy rainfall led to the flooding of a ravine a half mile from their home. Four people died (http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/44211953/ns/weather/t/dead-after-flash-floods-pittsburgh/#.T2tzbGL3tI4). Thirty minutes before the storm hit, I had driven through that same ravine. Our conversation that night hearkened back to the tsunami, as well as the closeness of the evenings call. I was no better at explaining the physics involved.

I didn’t think about whether we should talk about it or not. Not in the moment. I thought about it afterwards, I suppose. The questions every parent asks: Did I say that well? Did I answer all their questions? Do they have some bizarre idea in their head, because I wasn’t clear? Will they look back and remember these conversations with any importance?

Keeping it from them was never an issue. I lean toward the free range end of the parenting spectrum. It’s how I grew up. Besides that, one grandfather has been living with two different kinds of leukemia for ten years. Last year, the nice man across the street committed suicide. Their parents are divorcing. The parents of three other school friends already have. Their Dad had a stroke. A friend of mine whom they know lost her grandmother and father in the space of two weeks. There’s more cancer, and yesterday at my daughter’s school EMT’s came because a classmate had a particularly bad seizure. I could add the dog, a number of gerbils, and schools of fish to the loss they’ve experienced. This is life.

“Is that enough, or do you want to know more?” That is perfect phrasing. Last week I met my friend’s twin daughters for the first time. I made sure I brought my daughter. That’s life, too.

March 24th, 2012 at 1:27 pm

[…] >more […]