The Plastic Question

The girls seem to have forgiven me for breaking the news about Santa Claus, but this means that their Christmas wish lists are now addressed specifically to me. At least the dialogue has changed. I always felt uneasy perpetuating the you’d better be good because Santa’s elves are watching myth. Our discourse now is a more rational one about how many toys you really need and the  difference between having things and doing things. Last year we took a trip over the holidays, so the gift booty was limited to just a few items before we left and one or two things to open on Christmas day. De-facto and I kept repeating how the biggest present was the adventure we were having together. Short-pants bought into this idea completely. Buddy-roo was happy to have the trip, but felt her Christmas had been a little thin.

difference between having things and doing things. Last year we took a trip over the holidays, so the gift booty was limited to just a few items before we left and one or two things to open on Christmas day. De-facto and I kept repeating how the biggest present was the adventure we were having together. Short-pants bought into this idea completely. Buddy-roo was happy to have the trip, but felt her Christmas had been a little thin.

It started, this season, with Short-pants’ initiative to create her Christmas list, delivered to me with a disclaimer that it was a long list so I’d have choices; she didn’t expect to get everything she’d asked for. She’d written down about a dozen specific book titles, plus a Spanish dictionary and an herb book (?). Short-pants is always the easiest to shop for; a few balls of yarn and a book and she’s delighted. But that’s her chemistry. She slept on a mattress on the floor, and kept her underwear and socks in shoe boxes for the first two months we lived here. When I finally got her a bed and a dresser she threw her arms around me in appreciation. About the bookshelves I bought for her, she said, “Mama, that was more than I ever imagined to have in my room.”

Once Buddy-roo saw her older sister’s note on my desk, she needed to write one, too. The objects of desire on her Christmas wish list are considerably different: a Barbie dream house (with an elevator), the Playmobile castle (at 197 euros: ouch!), an iPod Touch, an iPad Mini, and a dog. For her birthday, just last month, we gave her a the simplest iPod, the iPod Shuffle, pre-loaded with songs I knew she’d like (Best Song Ever) or that I thought she should like (Bohemian Rhapsody). My strategy is to inch her into the technological gadgets, stretching our budget, and her attention span, as long as possible. Last year for her birthday she begged for a manual typewriter, which was no simple task to procure. The reason she still uses it as that she doesn’t have so many other toys to distract her. But despite her love for this new little iPod – it’s great to see and hear her with her earbuds on, rocking out with herself – she always asks for more, bigger and better. It’s in her nature. She always wants what she doesn’t have.

We’ve tried using her hunger for things as an incentive for doing her school work, but it always backfires. The reward we promise isn’t based on grades or scores, it’s about being responsible about her homework, bringing home the right  books, getting started on her own each night without whining or dilly-dallying. She starts out all excited, inspired that simply by being conscientious she might get that dollhouse, or that gadget, or a dog. Three days later, fatigued by the effort, she gives in to her lazy impulses and proclaims that she’ll never get what she wants because the work is too hard and it’s not fair and we’re the cruelest parents in the world.

books, getting started on her own each night without whining or dilly-dallying. She starts out all excited, inspired that simply by being conscientious she might get that dollhouse, or that gadget, or a dog. Three days later, fatigued by the effort, she gives in to her lazy impulses and proclaims that she’ll never get what she wants because the work is too hard and it’s not fair and we’re the cruelest parents in the world.

Which was fine with me in the past because I didn’t really want to give her any more gadgets or any more toys with little plastic pieces, and our apartment was too small for a dog. But now I actually would like to have a dog and here in Barcelona we live close to the mountain, which means a great, open, outdoor place where a doggie could run and frolic and do what dogs are supposed to do. But we can’t reward her current school behavior so at the moment we are pet-less.

~ ~ ~

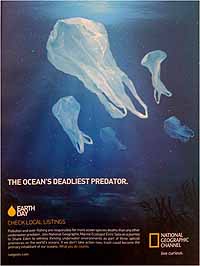

Two new friends from Buddy-roo’s class have invited her to work with them on an exposé for extra-credit. The subject they’ve chosen to explore: the large toxic plastic island forming and floating in the Pacific ocean. Her research involved collecting images for their poster board – leave it to Buddy-roo to volunteer to do the easiest part – so I set her up at my computer and she clicked on Google images to search for pictures of the floating plastic. What she found was disturbing: a mass of plastic containers, bottles and bags, partly deteriorated by the salt and sun but never fully degradable, pressed together in the middle of nowhere by ocean currents, forming a continent of debris that is killing the wildlife around it and bleeding toxic chemicals into the sea water and into the fish that are eaten by the fish we eat.

We scrolled through the images, selecting the ones she wanted to print and show to her schoolmates. She was disgusted by the volume of plastic garbage that has accumulated. She kept scanning through the images, horrified by the photographs of animals choked by or wrapped in pieces of plastic. It was the turtle whose shell was malformed – it looked as though it had a Barbie doll waist because it had grown within the ring of a plastic six-pack carrier – that made her cry.

“Those poor animals,” she said, tears streaming down her cheeks, “how can we let that happen?”

I didn’t have an answer.

It must have stayed with her all night, those images, that question. The next day, on the way to school, she brought it up.

“How come they keep making all that plastic? It’s killing the animals. Why don’t they just stop?”

“It’s all about money,” I told her.

It made me think of The Graduate, when Benjamin, who has no idea what to do with his future, is cornered by one of his parents’ friends offering unsolicited advice: “One word. Plastics.”

“Money?” she said.

“I bet you the men who run those big plastic factories were outraged about the pollution on the planet when they were ten years old, just like you are. But then they grew up and got jobs and got married and had families they had to support. Little by little they forgot what they knew when they were ten, and they started taking jobs and making decisions based on how much money they could make, because they wanted buy their kids what they needed: food and clothes and toys…like big, expensive dollhouses, made out of plastic.”

We walked along quietly. I could tell she was thinking about it, weighing her anger at the mounds of plastic in the ocean and what it was doing to our environment with her ardent desire for that overpriced plastic dollhouse.

“If you buy me that that castle, or that dollhouse,” she said, “I’ll play with it for years, and I promise to recycle it.”

We’d arrived at the gate of the school courtyard. She reached up and kissed me before running in to find her friends. I watched her as she joined their circle, opening her school bag to show them the images we’d printed,  telling her friends, I gathered, about the research she’d done. You could see the anger and sadness on her face. She was animated, outraged. But is she outraged enough to stop asking for plastic toys?

telling her friends, I gathered, about the research she’d done. You could see the anger and sadness on her face. She was animated, outraged. But is she outraged enough to stop asking for plastic toys?

Are any of us outraged enough to stop using plastic? Even if we are, can we slow or stop its production? Could we function in this plastic-wrapped society without ever touching plastic? The throw-away economy promised us convenience and delivered. But what do we do, now, with the environmental mess it’s created? That’s another question I can’t answer.