The Devoir

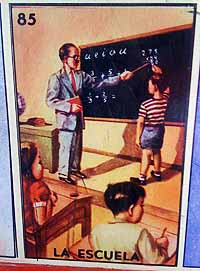

I pressed my knees together and wedged them under the tiny desk, perfectly sized for a nine-year old but more than a tight squeeze for me. The other parents, their long legs jutting out into the aisle and chairs pushed back to accommodate adult-sized thighs and bottoms, looked just as uncomfortable. I suppose hosting the parent-teacher meeting in the children’s classroom gives us a sense of their day-to-day environment, but it does put parents at a disadvantage. Hunched over and stuffed into hobbit-sized furniture, it’s hard not to feel like we’re back in school, cowering under the teacher’s strict supervision.

but it does put parents at a disadvantage. Hunched over and stuffed into hobbit-sized furniture, it’s hard not to feel like we’re back in school, cowering under the teacher’s strict supervision.

I remember in grade school, every year, on a night in early autumn, my parents would go to school after dinner for a meeting with my new teacher. During the day, we’d have been given a few minutes to arrange our books in our desks and we’d all work to tidy up the classroom. My father would always return from these meetings shaking his head with feigned disappointment. “Your desk was a terrible mess!” he’d say. The next day, I’d find my notebooks and papers turned sideways and mixed around, the handiwork of my father. Somehow I can’t picture his long legs bent under my primary school desk – I think it was more of a standing around, open-house kind of meeting – but I can picture the smile on his face while he was making mischief inside my desk to complete what was his very predictable annual prank.

These school meetings are important because you actually get to see and hear the teacher. French schools are very much drop-your-kids-at-the-door-and-stay-out-of-our-way. Last year, aside from the initial school meetings, Short-pants’ teacher never once spoke to me, and Buddy-roo’s rather humorless teacher and I had only a handful of exchanges, mostly about logistics. At these meetings you also get data that you might not otherwise pick-up, like how that sheet of paper that you thought was scrap and almost threw out is actually the assignment to research and prepare an oral presentation on Vikings, due next Monday. And with some assurance, you get to see that the other parents – even the fully French ones – are just as overwhelmed by it all as you are.

As the teacher described the work that would be required for each subject, I sank lower and lower in Buddy-roo’s already low-to-the-ground chair. The school meeting is like the door to summer slamming shut behind you. Gone are the blissful evenings of after-dinner walks for ice-cream and a family game of Mille Borne. Now our nights will be spent conjugating verbs, memorizing math tables and reading about Merovingians and Carolingians. The curious what-do-you-feel-like-doing-tonight? is replaced with the commanding fait tes devoirs. The word devoir means to have to, an auxiliary verb that means must or ought. When used as a noun, it can signify an obligation or a duty, or, as in this case, homework. Plenty of it, despite everyone’s complaints and the feeble call to ban it.

So far Buddy-roo’s devoir has been rather reasonable. But supervision is still required. Not so much on the three math problems due for tomorrow, but on the tricky “look-ahead” assignments: the test for next Wednesday which requires more than Tuesday night’s review, or the poetry every other week, which takes several evenings of practice to be able to recite by heart. It is still beyond the capacity of my 9-year-old to take responsibility for anticipating the due dates of these longer-terms assignments. As far as she’s concerned, next week is ages away.

Every evening, then, after a compact day of anticipating my own deadlines and strategizing how to get everything done in time, I find myself having to anticipate their deadlines and strategizing how to get everything done in time. I must survey Buddy-roo’s agenda and manage her homework, pressing her to start memorizing earlier rather than later, to cement her appreciation of Clovis and Pepin the Short and Charlemagne and to place them via historic timeline and accomplishment tonight, even though the test isn’t until next week.

Short-pants is more self-reliant, but she still needs nudging. Her speech on someone she admires wouldn’t have been completed in time had I not elbowed her, twice, to get started on the script. Her science report, identifying and describing the three types of tree leaves she was asked to collect, requires a decent amount of research and it was at my behest that she got started early. I get to be the raised eyebrow behind them both, with my new mantra, “I know it’s not due until next week, but you need to do a little every night…”

Some of the assignments seem, to me, beyond Buddy-roo’s capacity to be finished independently. Then it really starts to feel like homework for me. Maybe I should leave her alone, and let her sputter through and suffer the consequences of failing, but that’s not going to teach her how to do the assignment or help her learn the content. So I give in and help, always starting out as the facilitator, “Why don’t you read those paragraphs and then tell me how you’d summarize it in your own language?” Two hours later, I end up not-so-gently suggesting the answer so we can just get on with it and go to bed.

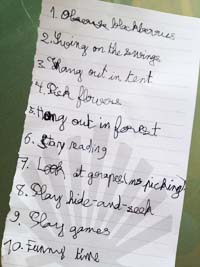

My greatest concern, beyond the burden this puts on me or De-facto, is the lack of time and freedom for them to imagine, invent and play. I remember coming home from school when I was in 4th grade and going for walks in the woods, playing with neighbors, making up stories and games, reading for pleasure. I rarely had homework at that age, unless it was a special report or project. My mother was happy to help because it happened once a month, not every night. My daughters, in contrast, sit at desks and work all day long, and then are compelled to use their evenings to do the same – and my evenings too.

I’m buoyed by the fact that Buddy-roo’s new teacher exudes warmth and compassion – a welcome change after the last year – and I think her classroom is going to be a much friendlier learning environment. But there are still a lot of musts that come along with the rules of a French classroom, so even though I considered re-arranging the books in Buddy-roo’s desk, just to mess the order up a bit and follow a family tradition, I decided, for her sake, I really musn’t.